As the global population ages, the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases, including primary tauopathies, is expected to rise—further underscoring the urgency for research and therapeutic development. Primary tauopathies are a group of neurodegenerative diseases where the tau protein, crucial for stabilizing microtubules within brain cells, malfunctions and accumulates abnormally. This misfolding and aggregation of tau is the primary driver of neurodegeneration, leading to a range of conditions such as Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP), Corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and Pick’s disease.

Conversely, tau pathology in secondary tauopathies is associated with other factors, such as amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The consequences for patients are profound, often involving progressive cognitive decline, movement disorders, and a significant reduction in quality of life. Unfortunately, there are no disease-modifying therapies available for targeting pathologic tau, leaving patients and their families with limited options and a critical need for effective treatments.

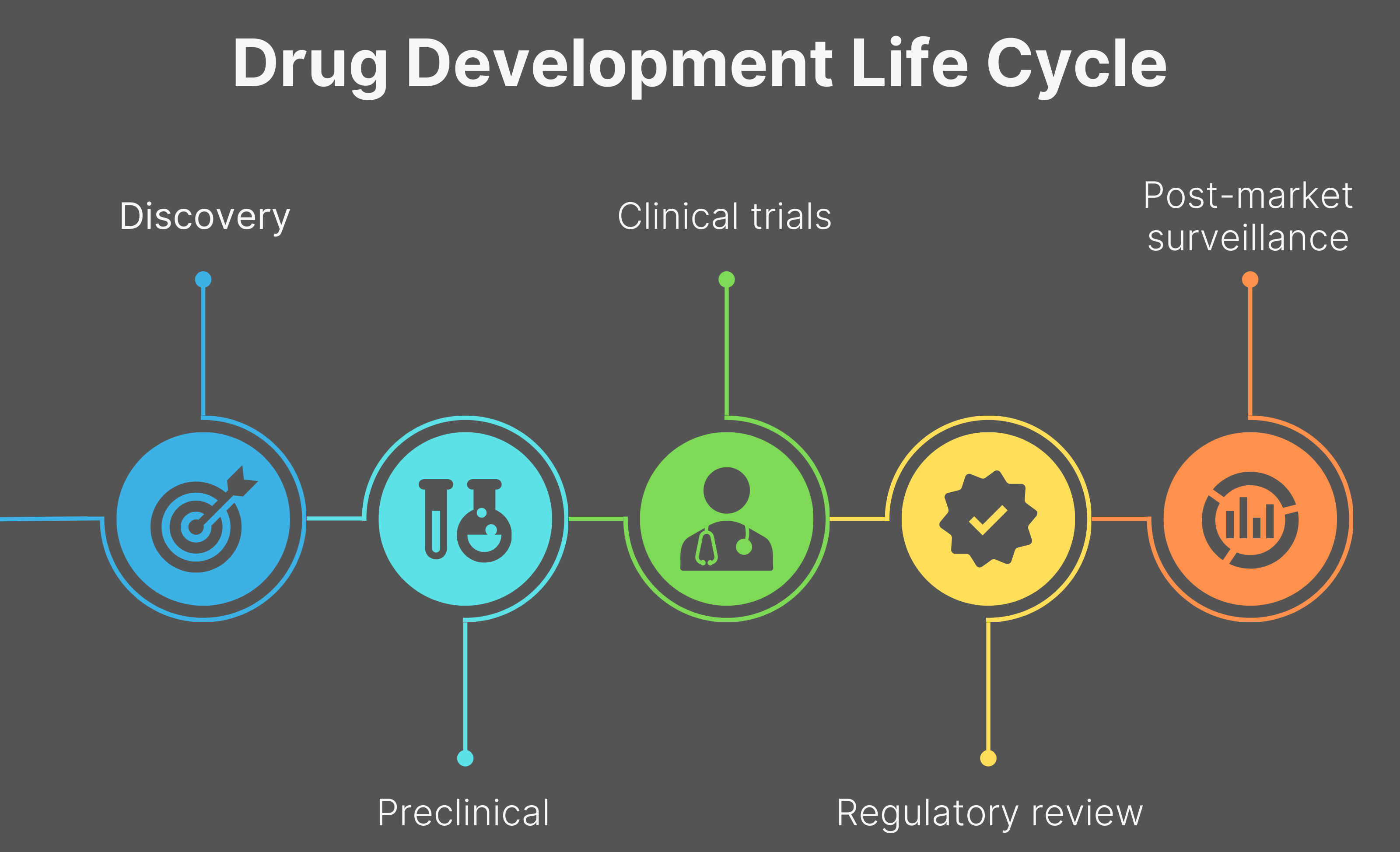

The journey of bringing a new drug to patients is both a long and complex process. It begins with the discovery stage where potential drug candidates are identified, followed by preclinical research, which involves lab and animal testing to assess the drug’s safety and efficacy. If preclinical studies yield promising results, the drug moves into clinical research, which progresses through multiple phases. Phase I trials assess safety and optimal dosage in a small group of people. Phase II evaluates efficacy and monitors side effects in a larger patient population, and Phase III trials are large-scale studies designed to confirm safety and efficacy, often involving hundreds or thousands of participants. If these trials succeed, the drug is submitted to regulatory agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for review and potential approval. Finally, post-market surveillance trials (Phase IV) ensure the drug’s ongoing safety and efficacy after it becomes available to the public.

It’s important to note that this entire process has a very high attrition rate, with only a small percentage of drugs successfully navigating all stages to reach patients. This lengthy and challenging path typically spans a decade or more and demands substantial financial investment, frequently reaching billions of dollars.

Drug Discovery’s “Valley of Death”

A critical bottleneck in the drug development pipeline, particularly for neurodegenerative diseases, is known as the “valley of death.” Lying between the preclinical and clinical research stage, this term describes the significant obstacles scientists face when translating basic research into therapies suitable for human testing. Many discoveries from academic laboratories stall here, lacking the necessary funding, expertise, and resources to progress.

A major obstacle in bridging this valley is the difficulty of translating results from in vitro (lab settings) and in vivo (animal models) studies to the intricate physiology of human diseases. The complexity of neurodegenerative conditions, coupled with the limitations of current preclinical models in accurately replicating the human disease course, contribute heavily to this translational gap. Consequently, many potential therapies that show promise in the lab fail to demonstrate efficacy or safety when tested in humans. The lack of sufficient funding during this preclinical period means that potentially life-saving treatments for primary tauopathies may miss the opportunity to advance to clinical trials.

Philanthropy’s Role in Drug Discovery

Strategic support and funding, particularly from nonprofit organizations, play a pivotal role in successfully navigating the valley of death and fueling the development of tauopathy treatments. The Rainwater Charitable Foundation (RCF) and other nonprofits in this field have funded numerous research projects and grants to unravel the complexities of primary tauopathies and develop new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

For instance, the Tau Pipeline Enabling Program (T-PEP), jointly funded by the Alzheimer’s Association and the RCF, aims to advance the study of novel therapeutic targets that will accelerate the development of disease-modifying interventions for tauopathies. A total of 23 T-PEP grants have been awarded, several of which later achieved significant commercial milestones (e.g., Polku Therapeutics, Acurastem, DTx Pharma, and Eikonizo Therapeutics).

Furthermore, the RCF has been at the forefront of defining criteria for the neuropathologic diagnosis of PSP and has supported the launch of a new clinical trial focused on a novel tau PET ligand for non-AD tauopathies, in collaboration with nonprofit partners like CurePSP and the Michael J. Fox Foundation (Canada CT # 285091). While a definitive cure for primary tauopathies remains an ongoing pursuit, these examples illustrate the tangible progress towards discovering potential disease treatments and cures.

Nonprofits like the RCF support innovative, high-reward projects lacking the extensive preliminary data required to attract substantial federal grants or private investment. The RCF and other nonprofits in this field can rapidly adapt to emerging research areas, prioritizing key therapeutic targets or novel approaches. Furthermore, nonprofits foster collaboration among researchers across institutions and disciplines, facilitating critical knowledge and resource sharing to address the complex nature of tauopathies. Some nonprofit organizations have adopted venture philanthropy models, strategically investing in for-profit companies to accelerate promising therapies. This multifaceted approach helps to mitigate risks in early-stage research, bridge the funding gap in the valley of death, and ultimately increase the number of potential treatments entering the drug development pipeline.

Nonprofit organizations also play a crucial role in de-risking early clinical trials by providing essential funding and advice. They help offset costs related to manufacturing investigational drugs, recruiting and monitoring participants, and conducting thorough data analysis. Government funding initiatives like the FDA Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grants Program and National Institutes of Health (NIH)-supported programs like the Alzheimer’s Clinical Trials Consortium play a critical role in advancing research and development for these conditions. By supporting these high-risk early-stage studies, strategic funding paves the way for larger, later-phase clinical trials that are essential for bringing new treatment options to patients.

Looking ahead, the evolving research landscape offers hope as scientists explore various therapeutic strategies to target tau pathology. They are actively developing and validating reliable biomarkers for early and accurate diagnosis, monitoring disease progression, and assessing the effectiveness of potential treatments in clinical trials. Continued strategic funding remains vital to sustaining the momentum of research and translating scientific discoveries into meaningful treatments. By supporting organizations that fund this critical research, we can directly advance efforts to deliver more treatment options and restore hope to the tauopathy community.